The US has expanded its use of tariffs on imports from other countries and those countries have increased trade barriers of their own, directed at the US. Tariff use by governments around the world had been declining for many years, and it's unclear whether the tariffs represent a speedbump on the long road toward economic globalization, or a more significant detour.

That question matters because globalization has been one of the drivers of the strong performance of US stocks over the past several decades. It has also helped keep inflation low even as the US has continued to grow.

Uncertainty about what may happen next has helped unsettle markets. Investors have been selling assets they bought last year, based partly on unfounded expectations about the future direction of government policy. Against this backdrop, it's important to remember that economic growth and corporate profits have historically been far more important for financial market performance than have short-term policy shifts.

In this era of social media and the 24/7 news cycle, individual investors should resist the temptation to make decisions about their portfolios based on what unreliable sources say will happen next. Instead, they should remember that diversification remains the best approach to confronting market volatility, regardless of what might be causing short-term market moves. That means seeking broad exposure to stocks and bonds from many parts of the world and from a variety of industries.

Tariffs and taxes

Tariffs are taxes on goods and services imported from other countries. Throughout history, governments have used tariffs for a variety of purposes, including protecting their domestic producers, penalizing other countries for actions they disapprove of, and maintaining national security.

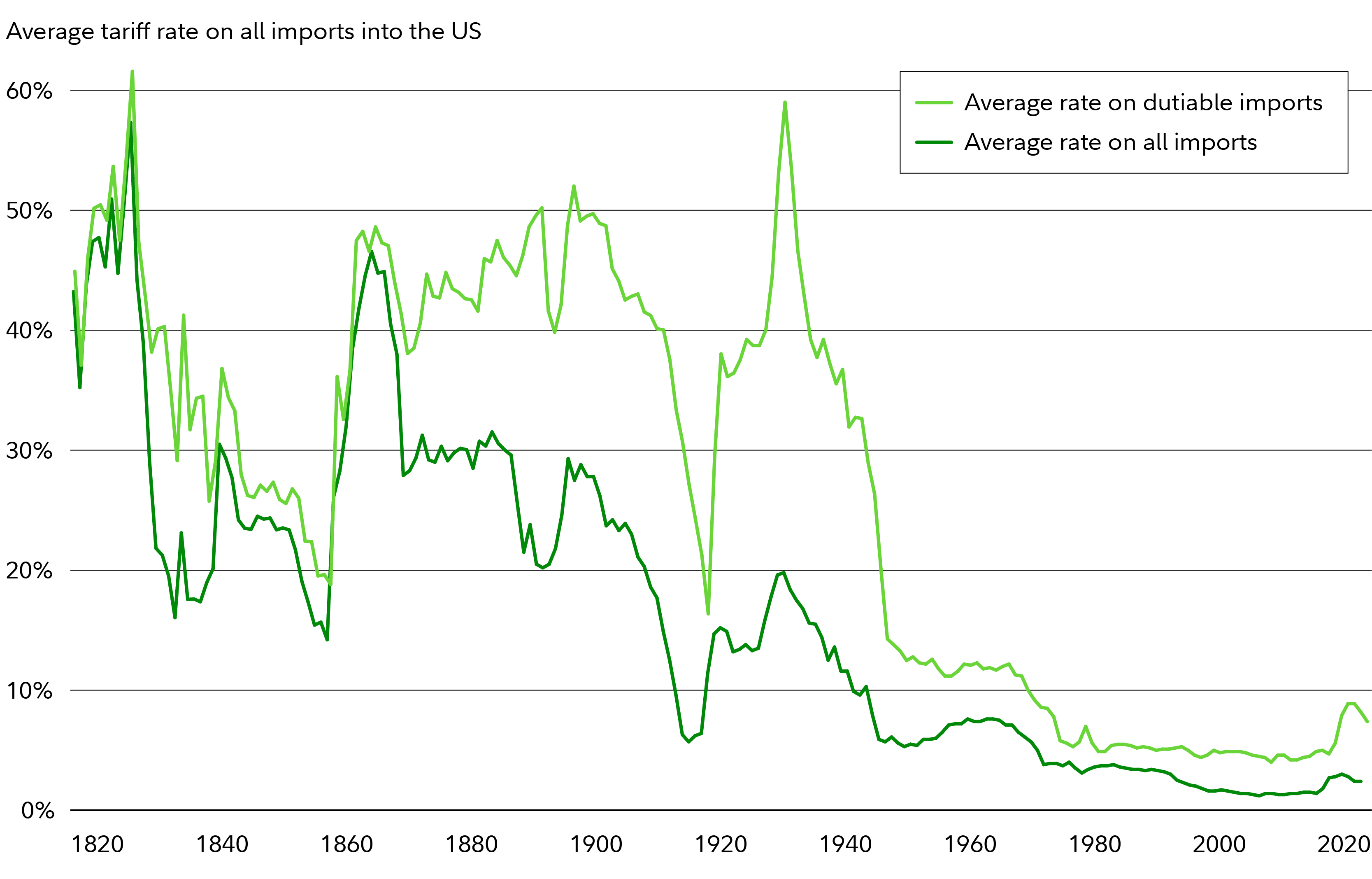

After the end of World War II, many of the world’s major economies signed an agreement called the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) that reduced tariffs in favor of policies that encouraged increased trade in goods and services between countries.

In the past decade, though, governments around the world have reconsidered the impacts of what is known as free trade and have adopted policies intended to benefit domestic industries by raising the cost of competing imported products. According to the International Monetary Fund, the number of new tariffs imposed by countries worldwide rose from a historic low of 239 in 2012 to 2,845 in 2023.

Are tariffs a new thing?

Tariffs fell out of favor from the middle of the 20th century until fairly recently, but the US government has a long history of using protective tariffs to benefit US industries. As early as 1789, a tariff on foreign sugar was imposed and tariffs on many other foreign products followed. In 2018, the US placed tariffs on $360 billion worth of imports from China in response to that country’s policies, which included pressuring US companies to give up their rights to their own intellectual property as a condition of doing business in China. Those tariffs are mostly still in place and last year, additional tariffs—some as high as 100%—were applied to another $18 billion worth of Chinese products, including steel and aluminum, semiconductors, and electric vehicles.

Who pays for tariffs?

Tariffs are paid directly to government tax authorities by companies when they import products or services into countries whose laws impose tariffs on those products. The amount that the importer pays is typically passed along to consumers of the products or services in the form of higher selling prices.

Advantages of tariffs

Proponents of tariffs say they protect existing companies and the people and communities that rely on them for jobs and income. For example, since 1964, the US has charged a 25% tariff on imported light trucks. The tariff was originally intended to penalize European governments that the US administration claimed were allowing European chicken producers to dump their products into the US market at artificially low prices. Since then, the so-called chicken tax has helped US truck manufacturers to continue to dominate the US pickup truck market, even as they’ve watched their share of the US car market (which is not protected by tariffs) shrink from 90% to 40% over the same period.

Tariffs may also help what Alexander Hamilton called infant industries to grow until they are able to compete with foreign rivals. This approach is evident in recent tariffs intended to encourage the production of medical supplies and semiconductors in the US, rather than continuing to rely on foreign sources for what are viewed as essential products.

Disadvantages of tariffs

Critics say tariffs do more harm than good by increasing the prices that consumers pay. However, the US tariffs of the past decade have not been accompanied by a sustained rise in inflation. When the US imposed its initial round of tariffs on China in January 2018, the US Consumer Price Index (CPI) stood at 2.1%. By mid-year, inflation had ticked up to 2.9% before dropping back to 1.9% in December for an annualized rate of 2.4%. Over the following year as trade tensions between China and the US continued, inflation in the US never exceeded 2.5% until the impact of COVID-related policies began appearing in 2021.

Despite the possibility of more tariffs, Fidelity’s Asset Allocation Research Team expects inflation to follow a “flattish trend” over the next year. However, they also say that returning to the stable, low inflation of the past 20 years will be “challenging.”

Tariffs are also often accused of harming the workers who might expect to benefit from them. In this view, because tariffs raise the prices of imported goods, domestic producers can also raise the prices they charge for raw materials. That raises costs for producers of finished goods who may be forced to lay off workers in order to remain profitable.

In addition, some believe that tariffs can slow economic growth. The Tax Foundation, which is generally skeptical of tariffs, says that the tariffs imposed by the US since 2018 are likely to reduce gross domestic product (GDP) by 0.2% and that proposed new tariffs could mean an additional 0.8% reduction in GDP.

What might the new tariffs mean for investors?

There will always be uncertainty if you are an investor. That makes it important to take a long-term view of your investments and review them regularly to make sure they line up with your time frame for investing, risk tolerance, and financial situation. Ideally, your investment mix is one that offers the potential to meet your goals while also letting you rest easy at night, regardless of uncertainty about political events.

We suggest you—on your own or with your financial advisor—define your goals and time frame, take stock of your tolerance for risk, and choose a diversified mix of stocks, bonds, and short-term investments that you consider appropriate for your investing goals.