Thanks to its potential to grow savings over time, the idea of compounding is what motivates many people to start investing. There are 2 main types of compounding: compound interest and compound returns. Here's how compound interest and compound returns work—and how you can take advantage.

What is compound interest?

Compound interest is when interest you earn in a savings account or on certain types of investments (think: certificates of deposit or fixed annuities) earns interest of its own. In other words, you earn interest on both your initial balance—called the principal—and the interest that's added to the balance over time. That's in contrast to simple interest, or when interest payments are based only on the principal. Any accumulated interest does not impact future interest payments.

How does compound interest work?

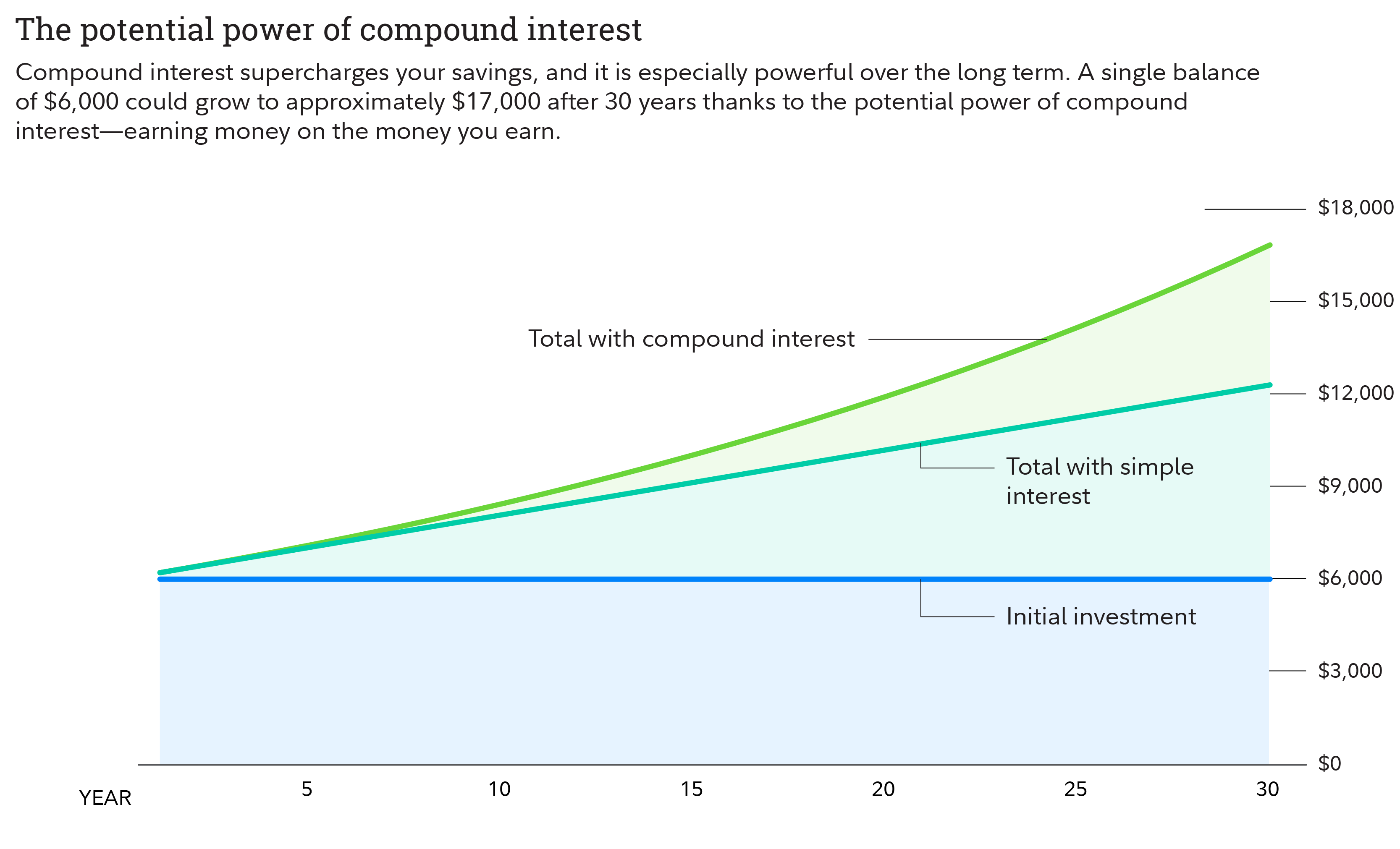

Compound interest takes advantage of previous gains to grow your money more. Need an example? Let's compare the difference between a $6,000 balance that earned simple interest vs. one that earned compound interest, assuming each earns a hypothetical 3.5% interest rate.

In year 1, you'd have identical balances: a $210 increase for a total of $6,210. A year later, simple interest would yield $6,420 ($6,000 + $210 + $210), and the compound-interest balance is slightly higher at $6,427.35 ($6,210 + 3.5% interest, or $217.35).

As illustrated in the chart below, over time the difference between simple and compound interest becomes more significant. After 10 years, a $6,000 balance earning simple interest would be worth $8,100. The same balance earning compound interest would total $8,464. And after 30 years, the difference is close to $4,500: about $16,840 for your compound-interest balance vs. just $12,300 for your simple-interest balance.

How to calculate compound interest

Final amount = Principal x [1 + (the interest rate / number of times it's applied per time period)]^(number of times it's applied per time period x the number of time periods that have passed)

Simple interest formula

Final amount = Principal + ((Principal x (1+interest rate) - Principal) x the number of time periods)

Compound interest vs. compound returns

Compound interest sometimes gets confused with another type of compounding: compound returns. While they sound similar, compound interest refers to interest calculated on both the initial principal and on accumulated interest of previous periods. This is typically viewed in the context of savings accounts, bonds, and loans.

Compound returns are a broader concept that includes compound interest, but also extends to other types of investment returns, such as dividends and capital gains. This is commonly used in the context of stocks, mutual funds, and other types of investment vehicles.

Compounding and your finances

Why is it important to understand how compounding works? In certain circumstances, it can work against you. That's because compound interest also often applies to interest added to credit card balances, which can make them harder to pay back. Aim to pay off high-interest debt as fast as you can to avoid having to pay back a lot more than you originally borrowed.

An important note: The frequency of the interest or returns you earn on your savings and investments and of the interest you pay on your credit card balance matters. For simplicity, in the example above, we assume compounding only happens once each year. In real life, it might occur daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, biannually, or annually. The more often it compounds, the greater compounding's impact.

How can investors receive compounding returns?

Anytime you invest money in the stock market, you're giving it a chance to benefit from compounding. Keep these tips in mind to make the most of compound returns.

Invest early

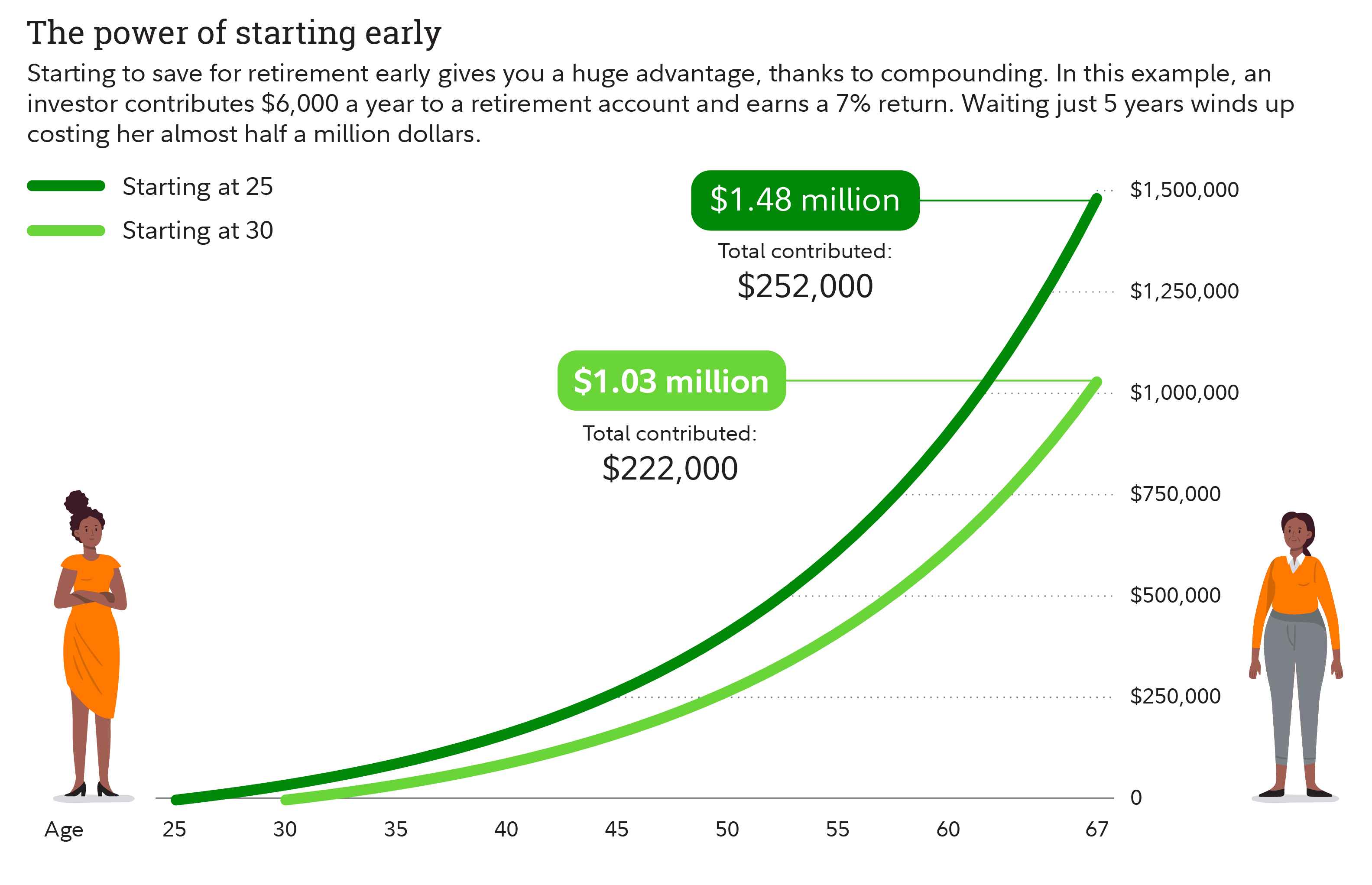

There's a saying in investing: "It's not about timing the market. It's about time in the market." That's because time fuels the potential power of compounding. Check out another example that illustrates what can happen for retirement savers who start investing early vs. those who wait.

Here's the difference just 5 years can make when it comes to saving for retirement. Two hypothetical savers invest $6,000 at the beginning of each year starting at either age 25 or 30. Each continues until they are 67 and earns an average 7% return. When the saver who started at 25 retires, her account balance is almost $1.5 million. The saver who started at 30? Hers is just over $1 million, or about $450,000 less, despite only investing $30,000 less than the early saver.

Of course, not everyone is able to start investing at 25 or has $6,000 a year ($500 a month) to set aside for their retirement. But this example shows how time can amplify investment compounding: Our early saver managed to grow her savings by nearly 500%. That said, over 37 years, even the later saver saw her investment potentially increase over 350%. The lesson? Start investing as soon as you can, even with small amounts.

Invest often

Investing regularly is one of the best habits you can build for financial success. Consider the difference between the total amount our hypothetical retirement saver who started at 25 might end up with if she had stopped after 10 years and never contributed another dollar.

Her account balance would be around $713,000. Considering she'd only invested $60,000 of her own money, that's not a bad return on investment. But it's also drastically less than if she'd invested over a longer time horizon.

Regular contributions have another potential: helping to decrease your risk. In our examples so far, we've relied on a hypothetical 7% average annual rate of return. This is a conservative value based on US large-cap stocks returning close to 10% annually over the last nearly 100 years. But the market doesn't move in a straight, upward line. Instead, there are peaks and valleys like bear markets, where stock values fall more than 20% from recent highs. Luckily, the stock market has recovered from every downturn it's experienced in history. It's important to remember though that past performance does not guarantee future results.

To combat this risk, many investors turn to dollar-cost averaging, a strategy that has you invest smaller amounts regularly rather than waiting to invest a large lump sum. (You likely already use dollar-cost averaging if you're saving for retirement through a workplace plan like a 401(k) or 403(b).)

Because you buy the same dollar value of an investment, no matter if prices are low or high, you buy more shares when prices are down and fewer when they're up. This strategy can help you avoid investing a lot right before prices drop or too little before they rise. In addition to helping minimize your risk, dollar-cost averaging may lead you to pay less per share on average over time.

But remember: Dollar cost averaging does not assure a profit or protect against loss in declining markets. For the strategy to be effective, you must continue to purchase shares in both market ups and downs.

Diversify

The average returns of US large-cap stocks are based on the returns of hundreds of public companies in the US. These wide-ranging holdings are designed to help provide the diversification that many investors aim for to decrease their risk.

While individual stocks may generate short-term, or even longer-term, returns that trump the broader stock market's (as represented by groupings like a collection of large-cap stocks), they also carry much more concentrated risk. The overall stock market has never zeroed out, but individual companies have.

By investing in a wide range of companies, any losses incurred by an individual investment in your portfolio may have a lesser impact on your portfolio overall. And if individual stocks you buy do stumble and fall, it's possible that others may rise to help balance it out.

But remember: The goal of diversification is not necessarily to boost performance—it won't ensure gains or guarantee against losses. Diversification does, however, have the potential to improve returns for whatever level of risk you're aiming to take on.

You can, of course, buy individual stocks yourself. But putting in the time, effort, and research it takes to pick them thoughtfully can be challenging. That's where mutual funds, index funds, exchanged-traded funds (ETFs), and target-date funds come in. With mutual funds, professionals do the research for you, either by conducting due diligence themselves or by simply aiming to duplicate the performance of a major market index, like the S&P 500. In either case, they strive to provide a diversified portfolio of many investments, with the goal of potentially benefiting from compounding.