How much did you make—or lose—on that investment? The answer lies in figuring out what's called your cost basis. More than just a point of pride, it is key to your capital gains tax bill. If you're savvy about cost basis, you can choose which shares to sell, which can ultimately help you lower your tax bill.

What is cost basis

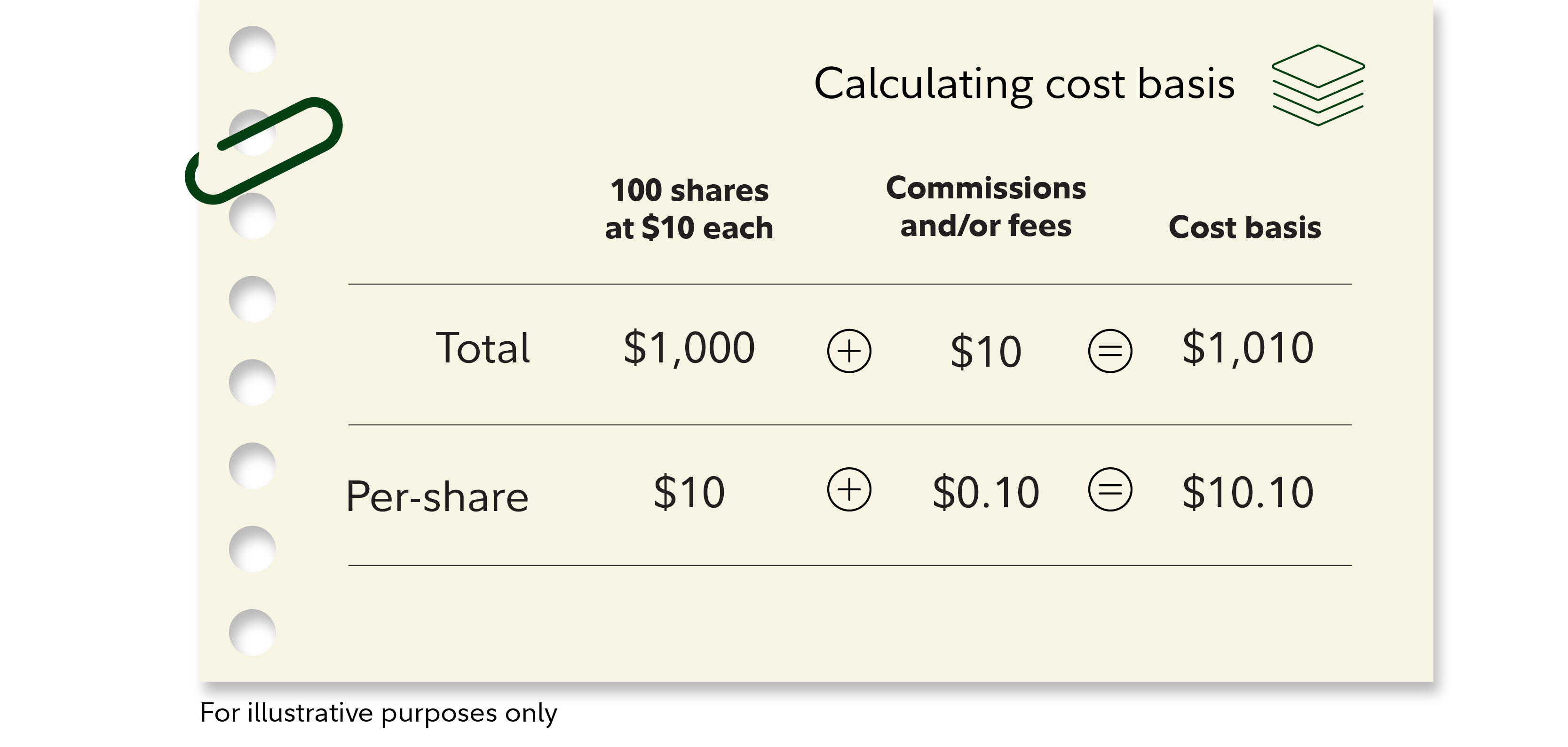

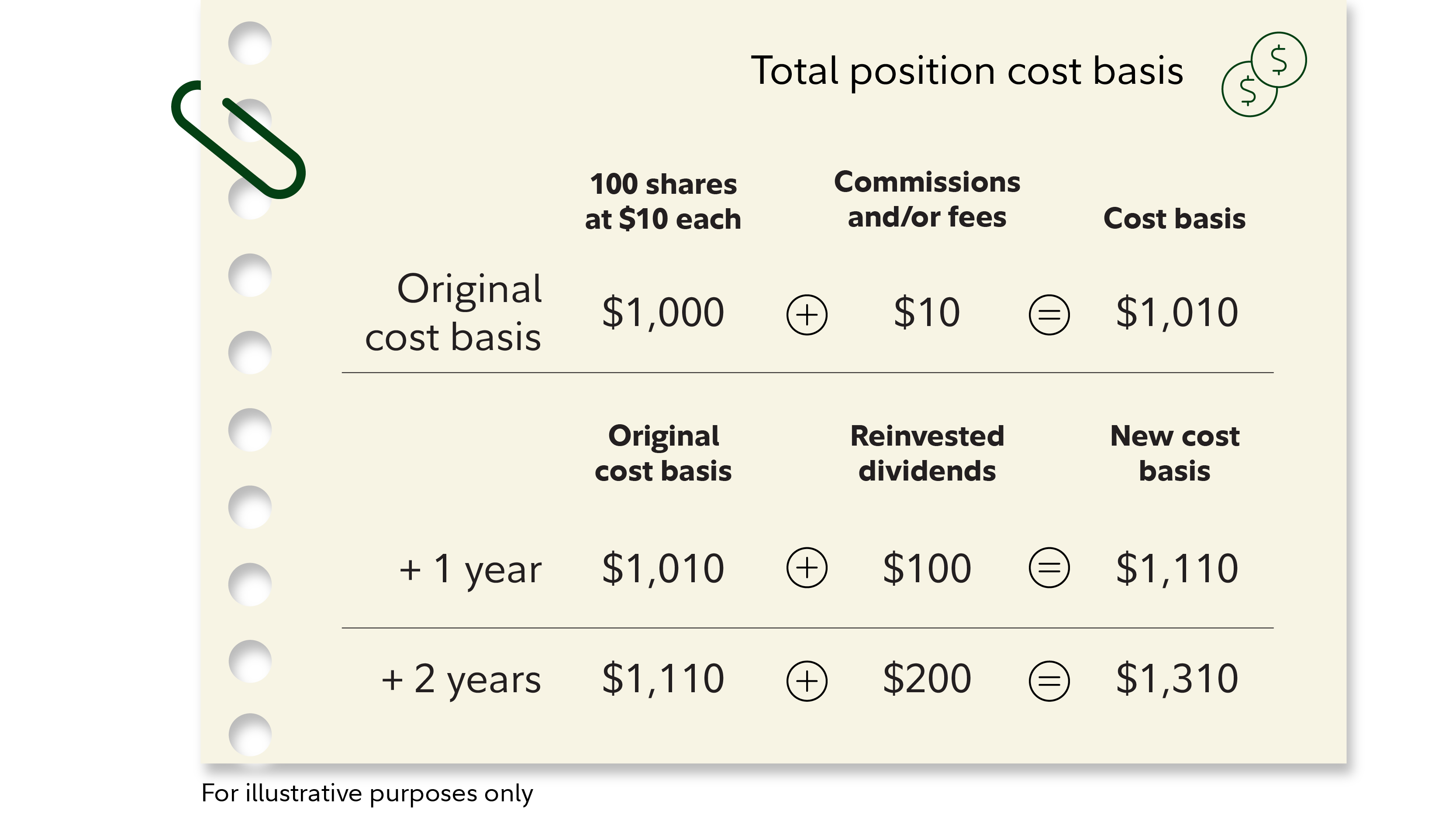

In a nutshell, the cost basis of an investment is the price you paid to purchase it, including any costs such as broker's fees or commissions. This can be expressed either on a per-share basis, or the total for your investment in the position.

Commissions are included in this example, but most brokers, including Fidelity, now offer commission-free trades.1

Why cost basis is important

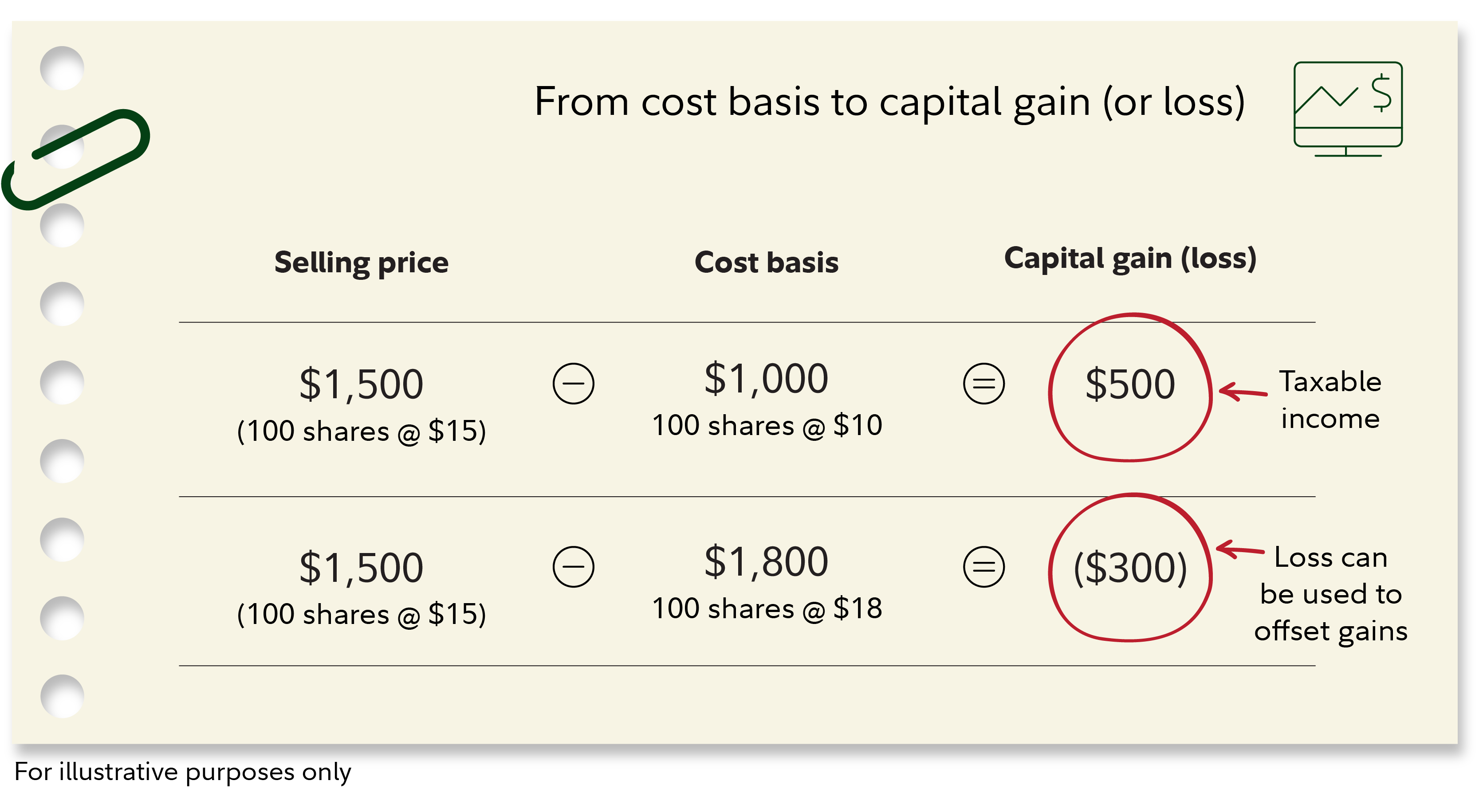

When you sell an investment for a profit, you generally owe capital gains tax. The way you figure out the gain or loss is to figure out the difference between your cost basis and your sale price.

How cost basis gets complicated

Cost basis can be pretty straight-forward: If you buy a stock today and sell it next week, its basis likely won't change. But if you hold investments for a while, lots of things can change your cost basis.

Reinvested dividends, stock splits, and capital gains distributions all can impact your cost basis. Bankruptcies and mergers and acquisitions also present complications. Here are 2 common events and how they affect cost basis:

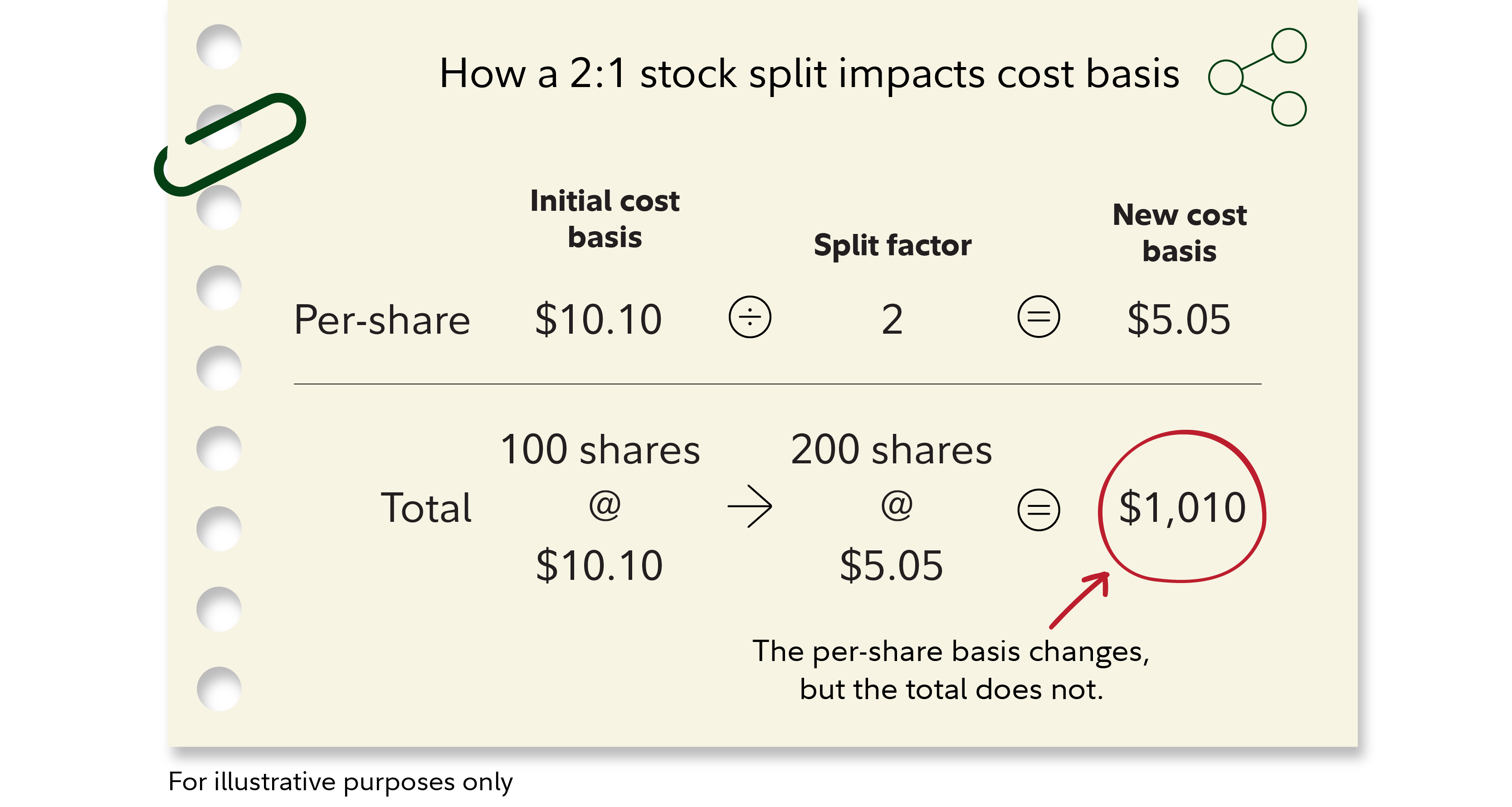

Stock splits: When a stock splits, the number of shares you own changes, but the total value of your investment doesn't change. This means your per-share basis changes, but not your total basis in the position.

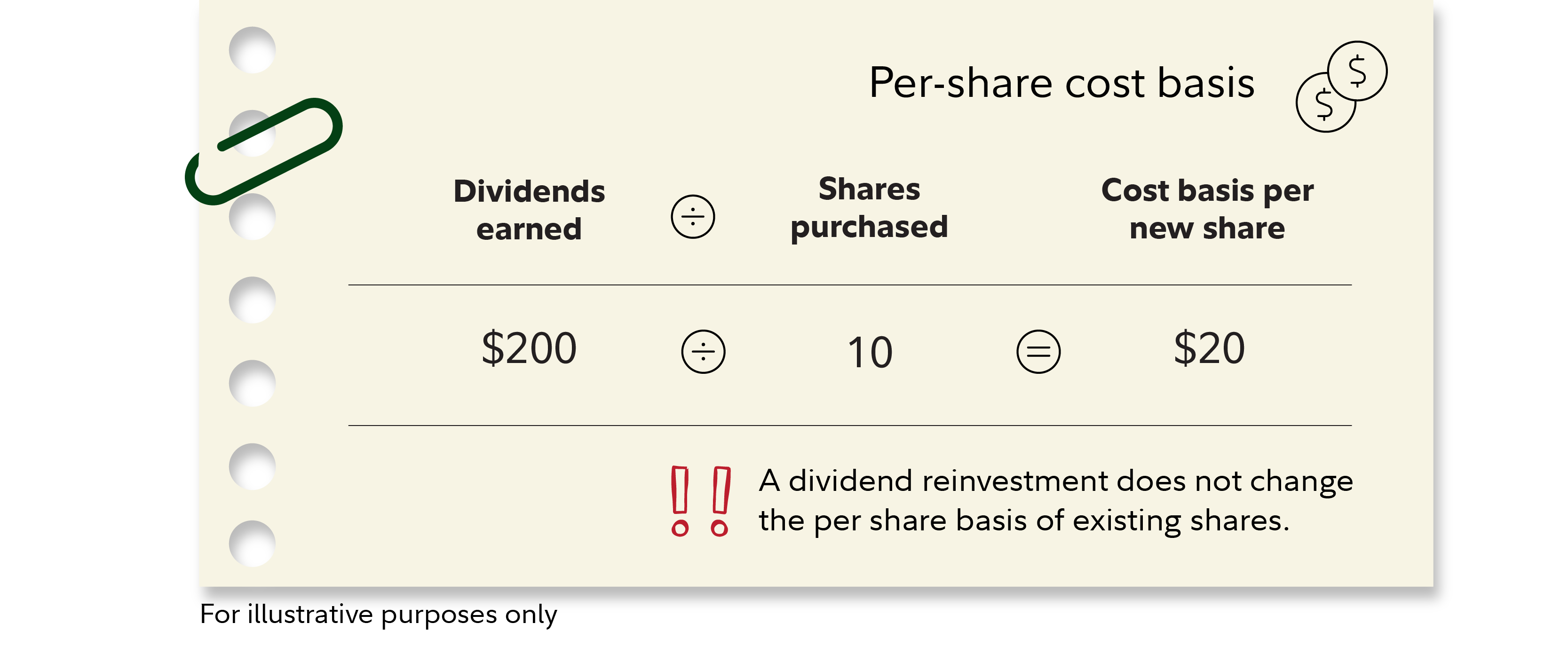

Reinvested dividends/capital gains distributions: Dividends and capital gains distributions that you receive in cash do not affect the basis per share of existing shares. When you reinvest dividends or capital gains, though, you are purchasing additional shares. The cost basis of your new shares will be equal to the price of the stock at the time it's purchased—adding more shares with a different cost basis from your original investment.

This may change the cost basis for your total position, but not the per-share basis of your existing shares.

How do I keep track of cost basis?

The good news is you generally don't have to keep track of all of this yourself, unless your investment dates back more than a decade. Brokers are required to keep these records of stock purchases in 2011 or later and mutual funds bought in 2012 or later.

Example of cost basis

Let's say you've been buying shares of a particular stock over the past few years. When you look at your position, you'll see a table that looks something like this:

Each line represents a tax lot—essentially, all of the shares in that position that have the same purchase date and cost basis. When you decide to sell shares, you can choose which lots to sell, and that's where you can save money on taxes.

How to use cost basis to lower your tax bill

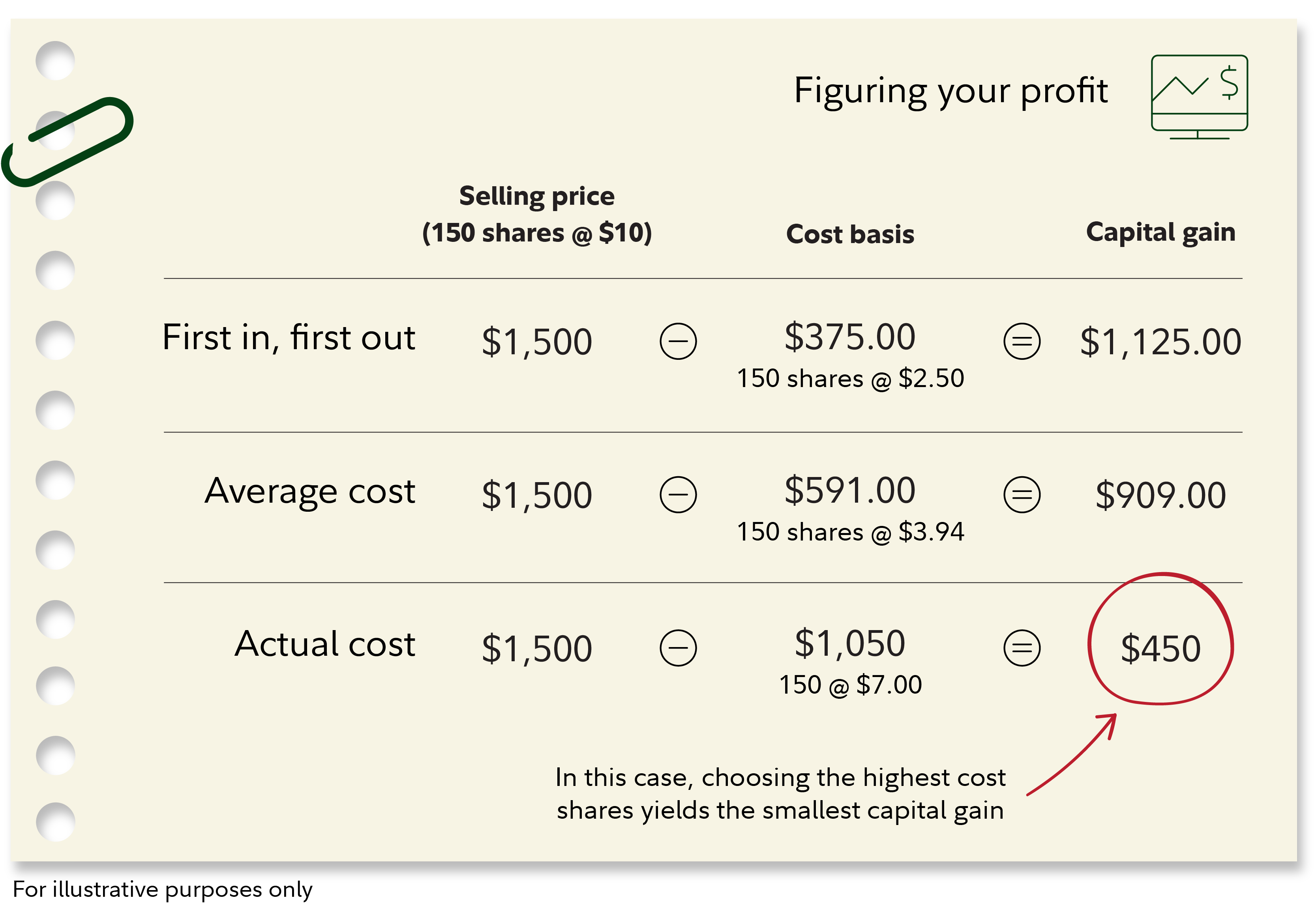

Now let's say you are ready to sell 150 of those Theta Inc. shares.

There are several ways you can calculate your cost basis, and they may have different outcomes for your tax bill.

Here are 3 common methods, followed by how each would change your capital gain for this sale:

First in, first out (FIFO): Shares that were bought first are also sold first. May result in larger capital gains.

Average cost method: This method takes the total cost of the shares and divides it by the number of shares.

Actual cost (specific shares) method: Your cost basis is the purchase price of each share. If you use this method, you can choose which lots are sold and potentially lower your tax bill.

By default, Fidelity uses first in, first out (FIFO) when selling shares of stock and average cost for mutual fund shares, but you can change your disposal method if you choose, either at the account level or at the time of a sale. Visit Cost Basis Information Tracking to see your cost basis information and account-level disposal methods.

Read more about how capital gains are taxed and see the current tax rates.

Our example only shows gains, but you can also use cost basis to choose to sell shares at a loss, which you can use to offset gains from other investments when you file your taxes. This is called tax-loss harvesting, and it can be a valuable tool. If that's your aim, then you can choose a method that would give you a greater loss.

Cost basis of gifted or inherited shares

If the shares you own were a gift or an inheritance, the rules are slightly different.

As a gift: You assume the original owner's cost basis—unless you ultimately sell them at a loss. In that case, use the fair market value of the shares on the date you received them to determine the loss.

As an inheritance: Your cost basis is the market price of the shares on the date you inherited them (the prior owner's date of death). Read more about inherited investments.

The bottom line

Cost basis can be complicated, especially if you're talking about shares you've held for a long time, or perhaps investments you've inherited.

If you have any questions about your true cost basis, consider talking to a financial professional, accountant, or tax lawyer.