A brush and paint together can create something beautiful. In the same way, steady contributions paired with the power of potential compounding can help your money grow in ways neither could achieve alone.

What is compounding?

Compounding means your investment returns can generate additional returns of their own. Over time, this snowball effect has the potential to turn small amounts into something much bigger.

Compounding interest vs. compounding returns:

- Compounding interest typically refers to fixed-rate products like savings accounts or CDs, where interest is added to your balance at regular intervals.

- Compounding returns applies to investments like stocks or mutual funds, where reinvested earnings—such as dividends—can grow alongside market gains.

Why do regular investments help boost compounding?

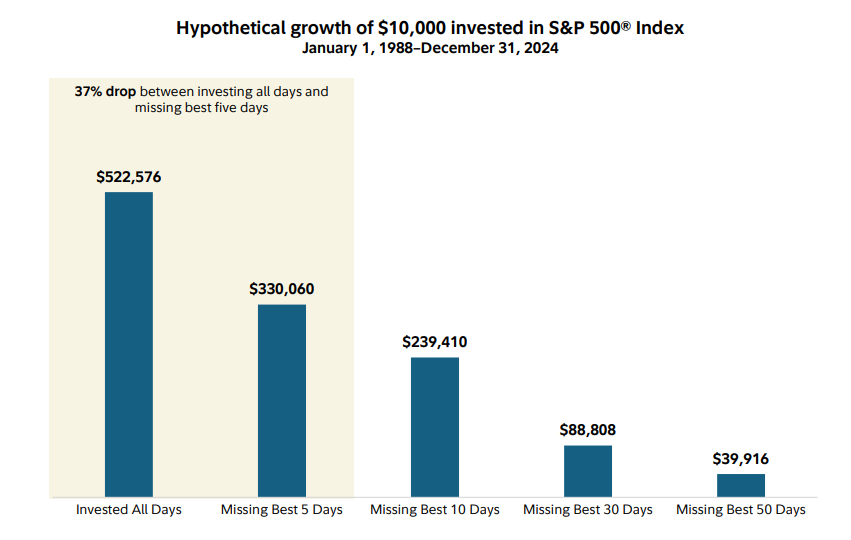

Adding money to your account regularly—every paycheck, every month, or on another schedule—can help you stay invested through market ups and downs and reduces the risk of trying to time the market.

The combination of steady contributions with the potential of compounding is a way of adding fuel to fire. Each contribution increases your principal, and any compounding accelerates growth by generating returns on both old and new money. Over decades, this combination can make a dramatic difference in your total balance.

The added boost of tax-deferred growth potential

Tax-deferred accounts—like 401(k)s and 403(b)s or traditional IRAs—can help supercharge compounding. Because you defer paying taxes on any earnings, more of your money stays invested and working for you. That means every dollar you contribute, and any dollars earned, have the potential to grow more than it could in a taxable account. Over time, this tax advantage can significantly increase your ending balance.

The power of time

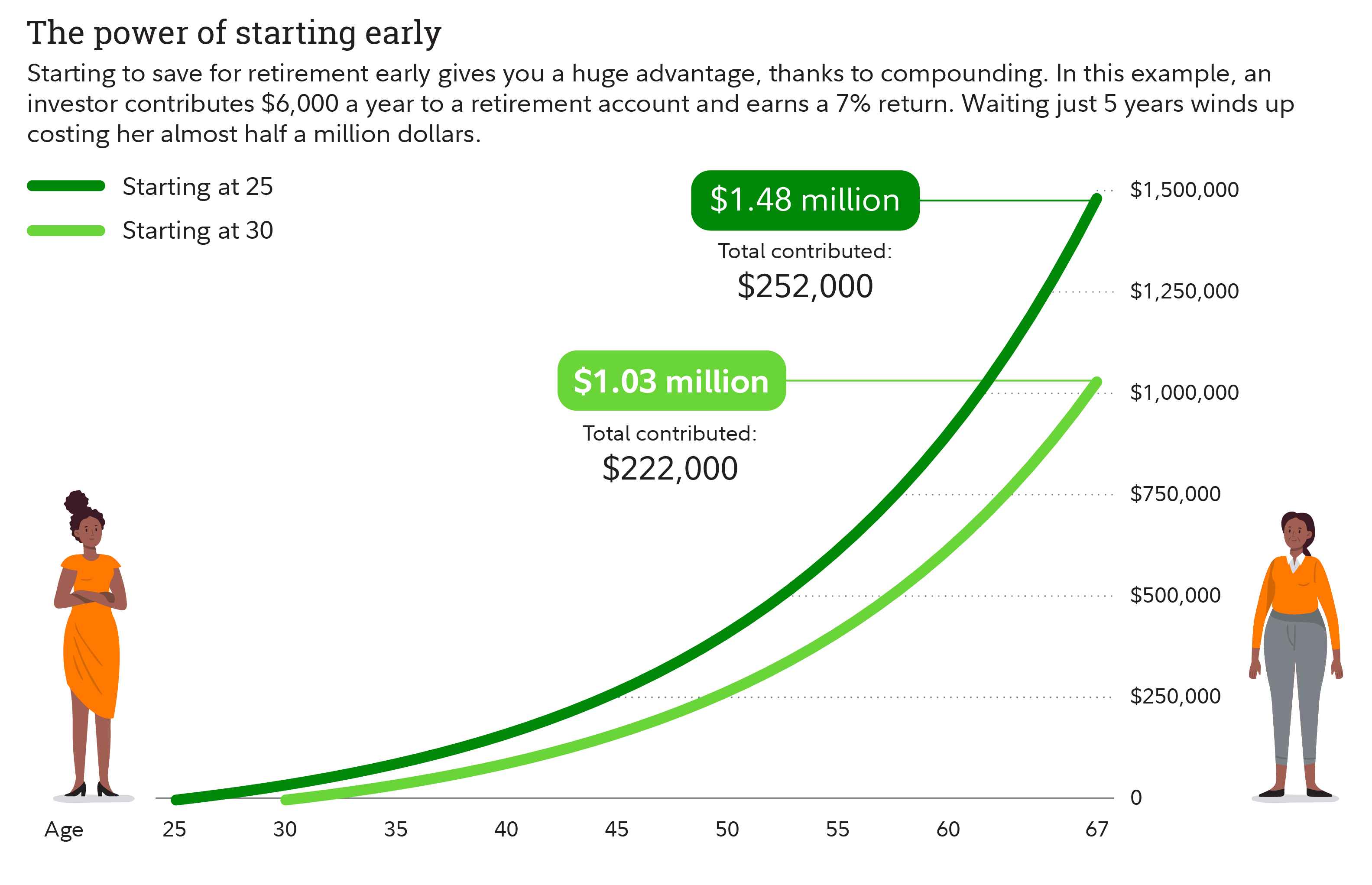

Time is the secret ingredient that makes compounding powerful. The longer your money stays invested, the more opportunities it has to potentially grow—and the more any earnings can generate additional earnings. Small contributions made early can outweigh larger contributions made later because they have more years to potentially compound. This can be why beginning to save for retirement early in life can be so effective. Starting sooner gives compounding more time to work its magic.

Practical tips to harness the combination

- Automate contributions: Setting up automatic transfers from your paycheck or bank account can help take the guesswork out of investing. Automation helps you stay consistent without having to remember each deposit—and it can reduce the temptation to skip contributions when markets feel uncertain.

- Use dollar-cost averaging: By investing a fixed amount at regular intervals, you buy more shares when prices are low and fewer when prices are high. This strategy can help smooth out the impact of market volatility over time and keep you focused on your long-term goals.

- Why consistency beats timing: Research shows that trying to time the market often leads to missed opportunities. For example, missing just a handful of the market’s best days over decades can significantly reduce your returns. Staying invested and contributing regularly helps you capture more of those good days.

Turn compounding into progress

Ready to put compounding to work? Explore Fidelity’s tools and calculators to see how consistent contributions paired with an appropriate investment strategy can help you reach your goals.