Nonqualified deferred compensation (NQDC) plans are typically offered by an employer to company officers and other highly compensated employees, enabling them to save more in a tax-advantaged account than is allowed under 401(k) plans. The ability to invest compensation pre-tax can allow for significant growth potential and federal tax savings. But what about state and local taxes?

Your NQDC plan distributions may be taxed at the state and local level depending on several factors, including:

- Where you live

- Where you work when your compensation is earned

- The structure of your NQDC plan

- Your distribution elections

Where you live

You may live in a different state at the time of distribution than the state you worked in at the time of deferral. Depending on the structure of the NQDC plan, the state where you worked and earned the money may apply what is known as a source tax.

But federal law bars states from taxing nonresidents on distributions from qualified retirement plans and some types of nonqualified plans (see Section 114(a) of Title 4 of the US Code). If this law applies to the NQDC plan, only your current state of residence can tax your NQDC distributions. Therefore, it may prove advantageous to move from a high-tax state, such as New York or California, to a lower tax state or to a state without income tax, such as Florida or Nevada.

But to avoid being subject to tax in the former state where the income was earned, the participant in the plan must opt to take payments in a specific way, which depends on the structure of the plan.

Excess benefit plan

Under an excess benefit plan, payments must be made after termination of employment to avoid being subject to tax in the former state where the income was earned. An excess benefit plan can provide benefits only when statutory limits related to qualified retirement plans, like a 401(k), have been reached.

This type of plan does not need to be paid out over 10 years or more, but it can make sense to take distributions over a number of years to spread out federal tax liabilities—potentially reducing the effective tax rate on NQDC distributions.

For example, Company A provides a dollar-for-dollar 6% matching contribution no matter what someone's compensation is. Under the rules of a qualified plan like a 401(k), the employer would be allowed to contribute only 6% of the annual compensation limit of $350,000 in 2025. So, the most the employer could contribute to a highly compensated executive would be $350,000 × 6% = $21,000. The employee could also contribute $21,000 plus another $2,500, up to the annual contribution limit of $23,500 in 2025. Note that plan limits are subject to change each year.1

Suppose an executive at Company A, who we'll call Employee B, makes $1,000,000 and plans to save 6% of their income, or $60,000, in 2025. Employee B contributes $23,500 to the 401(k) and $36,500 to the NQDC plan. The employer contributes $21,000 to the 401(k) and $39,000 to the NQDC plan.

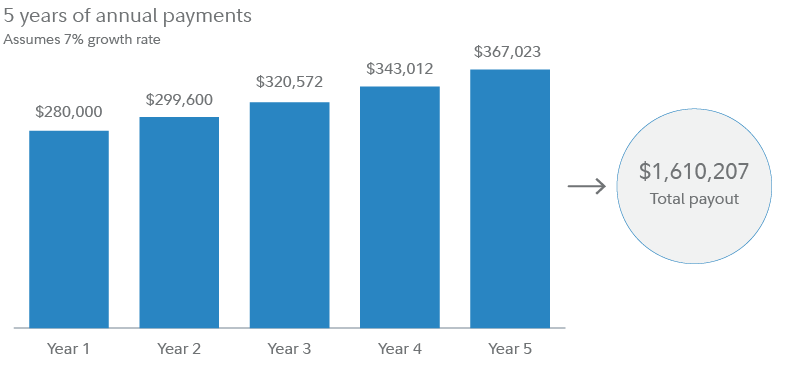

When Employee B retires, the NQDC plan has a value of $1,400,000 and pays out annually over 5 years, assuming a 7% annual growth rate.

So, what difference can state taxation make? In a worst-case scenario, the $1,610,207 could be subject to California's maximum tax rate of 13.3%,2 which would amount to $214,158. Of course, this is an example to show that state taxes matter. If you are enrolled in this kind of NQDC plan, or a similar type of plan, then you may benefit from retiring in a low- or no-income-tax state.

Note: State taxation in the state of residence (as opposed to the state where the income was earned) applies only to NQDC payments received after termination of employment when the nonqualified plan is an excess benefit plan.

Elective deferred compensation plan not integrated with any qualified plan

If your employer's plan is not designed as the type of plan discussed previously (i.e., an excess benefit plan), then how you elect to receive the deferred compensation on the designated payment date can impact your state tax liability. By electing to receive annual payments for a period of 10 years or more, your income under current law should only be taxable income in your state of residence.

Many NQDC plans will make distributions according to a 1/n rule, which is accepted as "substantially equal installments." For example, a plan making distributions over 15 years would distribute 1/15 of the balance in the first year, 1/14 of the balance in the second year, 1/13 of the balance in the third year and so on.

If you plan to move to a different state sometime in the future, you may want to elect a payout period of 10 years or more, particularly if some or all of that time you will be retired from your current employer and a resident of a lower tax state than the state you are working and living in now.

Be aware that electing a payout period of 10 years or more means that you would continue to be an unsecured creditor of your employer for that same period of time. You should consider the risk when making deferral elections.

It may not be necessary to extend the payments over more than 10 years in every case. For example, if you live in a state without an income tax and you earned/deferred income in that same state, you may not be concerned about state income taxes.

When—and where—payments are taxable

The examples that follow help illustrate when NQDC plan distributions are taxable in the source state (where the income is earned) and when plan distributions are taxable in the residence state (where the person is living when payments are received).

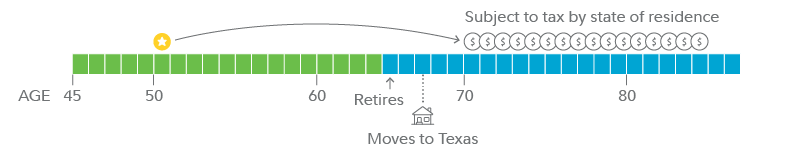

1) Executive moves to a different state before qualifying NQDC payments start

An executive at age 50 working in New York City defers income until age 70. She elects to receive substantially equal annual payments over a 15-year period. She later retires from the company at age 64 and moves to Texas at age 66. None of the 15 annual payments starting at age 70 would be subject to tax in New York City or New York State.

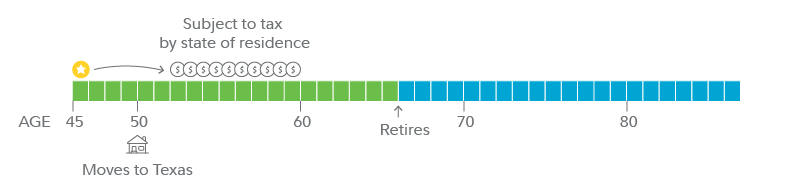

2) Executive retires after NQDC payments end

An executive at age 45 working in Los Angeles, California defers income until age 52. She elects to receive substantially equal annual payments over a 10-year period. At age 50 she moves to a different part of the company located in Texas and retires from the company at age 65. Since she elected to receive payments over 10 years and moved to Texas, none of her payments are subject to tax in the State of California.

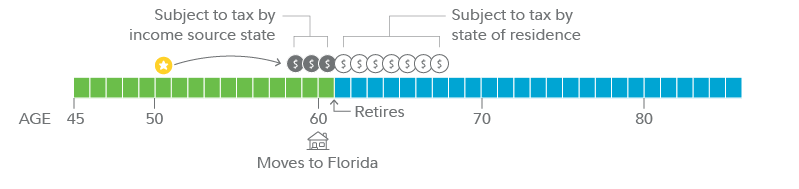

3) Executive retires after qualifying NQDC payments start but before payments end

At age 50, an executive working in Virginia defers a portion of her December bonus income until age 58, payable in annual installments over 10 years. She receives her first payment at age 58 in Virginia. She moves to Florida at age 60 and retires at the age of 61. While a resident of Virginia, her income will be taxable income in Virginia. When she moves and changes residence to Florida, her nonqualified deferred compensation benefits will no longer be taxable in Virginia. Her new residence state of Florida does not have an income tax.

4) Executive moves to a different state after qualifying NQDC payments start

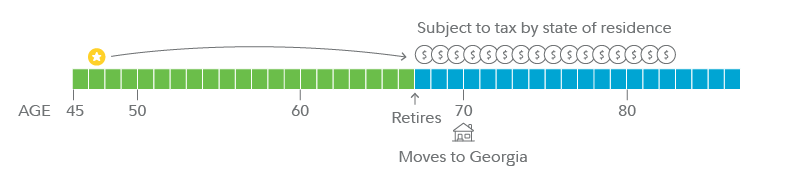

An executive at age 46 working in Illinois defers her bonus until retirement. She retires at age 66 while still living in Illinois, but at age 70 she moves to Georgia. Because she elects to receive more than 10 installments, they are taxed according to her state of residence. Her first several distributions are subject to tax in Illinois, but her later distributions are subject to tax in Georgia.

5) Executive elects installments over fewer than 10 years

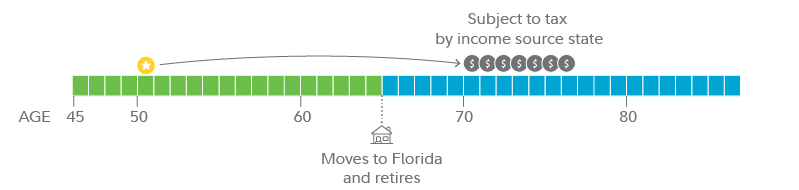

An executive lives and works in Massachusetts from age 45 to 65. At age 50 she defers a portion of her bonus, payable in 7 annual installments beginning at age 70. At age 65, she moves to Florida. Because she opted for fewer than 10 installments, her distributions are subject to Massachusetts state income tax.

Multi-state taxation of NQDC plans can be complex. If you're confused about the type of plan you may have, check with your employer's human resources department. A tax professional can guide you on managing your tax liability. Ultimately, you are responsible for correctly reporting your NQDC distributions.

State taxes matter

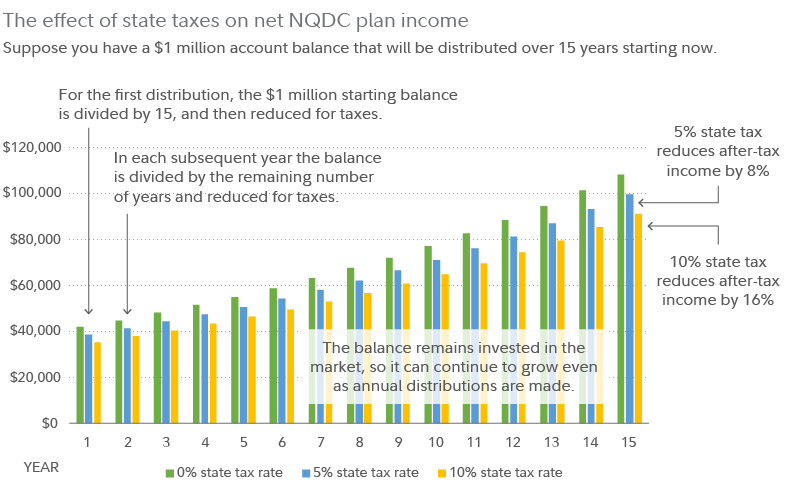

Sometimes state taxes matter a lot. Suppose you have a $1,000,000 account balance that will be distributed over 15 years, starting now. The first-year payment is the starting balance divided by 15 and then reduced for taxes. In each subsequent year we divide the remaining balance by 14, 13, 12, etc. For illustrative purposes we'll assume you are already retired and are in the highest federal income tax bracket of 37%. We'll also assume an investment growth rate of 7% per year. Let's look at the impact of a hypothetical 0%, 5%, and 10% state tax rates will have on your nonqualified deferred compensation benefits when they are paid.

In this example, a 5% state tax reduces after-tax income by 8%, and a 10% state tax rate reduces after-tax income by nearly 16%.

Because the impact of state taxes can be significant, it makes good sense to speak with a tax professional about your NQDC distributions and any potential tax bills.