What does it mean for bondholders when a company that issued their bonds becomes insolvent? The good news is that the US bankruptcy process offers them a variety of rights and protections that may increase the likelihood that they will recover the value of their investment. It's also good to remember that bankruptcy does not necessarily mean the end for a company or the securities it issues.

How bankruptcy works

Chapters 7 and 11 of the Federal bankruptcy laws govern how US companies go out of business or attempt to recover from financial distress.

When a company files for Chapter 7, it ceases operations and its assets are sold to repay creditors and investors.

Chapter 11 bankruptcy allows a company to reorganize in hopes that it may again become profitable. Once a restructuring plan is approved in court, the bankrupt corporation emerges as a newly organized company with less debt.

While either type of bankruptcy often means an investor loses money they had invested in the company's stock, investors holding bonds are much more likely to recover at least part of the value of their initial investment.

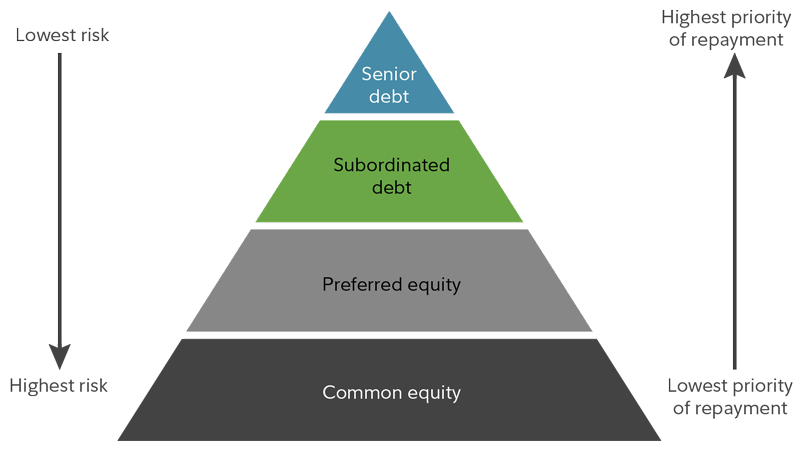

The fates of investors in bankruptcy are determined by laws which specify the order in which creditors are repaid. Like an airline gate agent directs passengers when to board a plane depending on whether they hold first class, coach, or basic economy tickets, a bankruptcy court divides creditors into groups with differing rights of repayment.

This hierarchy of repayment typically looks like this:

As the chart shows, senior debt holders (typically banks) get paid before all others. Bondholders are in the next group and a bankrupt firm often still has enough assets to pay them at least some of what they are owed.

But while where you stand in line helps determine when and how much you get repaid for your investment, how you are repaid may vary depending on the company's business, the assets it has, and its path out of bankruptcy. Once a company files for bankruptcy, bondholders no longer receive principal and interest payments. When the process is complete, they may receive newly issued bonds, cash, or stock whose value may not equal the value of the bonds they owned.

In a Chapter 7 bankruptcy, bondholders receive cash from a sale of the company's assets, a process that may take years to complete.

Government bonds and bankruptcy

Holders of corporate bonds are not the only investors who face the prospect of their investment landing in bankruptcy. Some governments, many of which faced financial challenges due to underfunded pensions for retired employees, now also confront reduced tax revenues due to the impacts of shutdowns.

Highly indebted state governments such as Illinois and New Jersey cannot declare bankruptcy. However, local governments in all but Georgia and Iowa have at least some ability to reorganize their finances. While defaults on municipal bonds have historically been rare, certain municipalities may find themselves on the path into bankruptcy that overextended governments in Detroit and Stockton, California traveled following the global financial crisis.

Detroit's 2013 bankruptcy after decades in which its tax base shrank is a cautionary tale for municipal bondholders. The bankruptcy court gave retired city employees priority for repayment and they recovered nearly 90% of the pension benefits promised them. Bondholders were given lower priority and recovered only about 80% of the value of their investment.

Losses like Detroit's bondholders experienced are somewhat less likely today because states have adopted laws which protect bondholders. For example, California, which has accounted for almost 30% of all city and county bankruptcies since the global financial crisis, has a law that places liens on future property tax revenues to ensure bondholders will be repaid.

What to do

A default or failure to pay interest to bondholders typically precedes bankruptcy, and a company will show signs of distress before defaulting. Credit rating downgrades, declining earnings, and other events can indicate problems. Bonds of issuers facing difficulties will also drop in price as markets become concerned with the issuer's ability to pay interest and principal. Investors should remember that the probability of downgrades and default increases according to how low a bond is rated, and higher-yielding bonds often have low credit ratings.

If you own a bond issued by a company or government at risk of default or bankruptcy, you face a choice between holding the defaulted bond through bankruptcy or selling it.

If you hang on, you face uncertainty over how much you will receive, and when you will receive it. If you sell, you'll know the amount you're getting. However, the amount you receive for selling before restructuring is complete can be less than both the amount you paid and also the amount you may receive if you hold on through the end of the bankruptcy.

Investing involves risk and research is an important part of managing risk. Fidelity's website tracks issuer events for corporate bonds and material events for municipal bonds, including downgrades and credit watches. Bondholders can also receive this information through email alerts which provide opportunity to react to news of a downgrade or negative credit watch should they wish to.

Other useful resources include Fidelity's Yield Table on the bond research page, which can compare 120 yields at a time.

More information is available in the transition rate table, which shows the probability that a bond will be upgraded or downgraded in a year's time. The lower the starting point in terms of credit quality, the higher the probability of further downgrades.

"We strive to provide investors with resources to research bonds and issuers before they invest," says Richard Carter, Vice President of Fixed Income Products at Fidelity. "It's important to know what you own and why."